Brooks Falls may be known for its fat bears, but this concentration of coastal brown bears (Ursus arctos) wouldn’t be here without the salmon. Relying on their sense of smell and internal GPS system, millions of salmon make their way from the open waters of the ocean back to their natal grounds. They must overcome obstacle after obstacle, with the Brooks waterfall, and the hungry bears in hyperphagia the last major hurdle before they can make their spawning beds.

A brown bear leaning down to drink water from a river, with rocks and blurred trees in the background.

A coastal brown bear (Ursus arctos), navigates the rocky shores of a glacier-fed lake in Alaska looking for a meal of salmon. In the fall, these bears are looking to put on as much weight as they can while burning as few calories as possible doing it. These last weeks of autumn, before the heavy snowfall blankets the landscape, are the bears’ last chance to put on enough weight to provide for their nutritional needs throughout hibernation.

Bear cubs will stay with their mother for two or three years. When the sow believes the cubs are ready to live on their own, she emancipates them, often going to great lengths to haze the cubs with charges, growls, and other defensive behavior to run them off. Siblings may stay together during emancipation before eventually living a solitary life.

An Alaskan coastal brown bear swimming in a body of water with its head and eyes above the surface, reflected in the water.

Though brown bears mate in summer, they have delayed implantation. This means that the fertilized eggs (blastocysts) remain dormant and do not attach themselves to the uterine wall until conditions are better for birth. This means bear cubs are born during hibernation, while the sow is still in her den. Bears mate with more than one individual, which means that cubs born at the same time may have different fathers, supporting genetic diversity for the species.

Coastal brown bears (Ursus arctos) will often fish in the ocean while waiting for the salmon to begin their run up the rivers. Bears are excellent swimmers and will often employ a "snorkeling" method of fishing, putting their faces in the water to find fish before pouncing on them.

Cook Inlet in Anchorage, Alaska, experiences dramatic tide fluctuations, sometimes as much as 35 feet. When there is a large tidal swing, coastal brown bears take advantage of the exposed area to dig for razor clams—a favorite protein source while awaiting the return of the salmon.

Mothers of black bears (Ursus americanus) often send their cubs up in "nursery trees" while she goes off to forage and hunt. This helps keep them safe from predators, especially boar bears, who are known to kill cubs specifically to send the sow back into estrus so he can mate with her. When the sow returns, she utters a guttural call to her cubs to bring them down from the tree to move on.

When the summer sun blazes, black bears (Ursus americanus) have clever ways to stay cool. Despite their thick fur, these adaptable mammals know how to make the most of their environment. They often seek out shady forests, dense underbrush, or cool caves during the hottest parts of the day. This bear chose hanging out in a tree, higher up to catch the breeze, as his way of cooling off in the normally cool boreal forest. And yes, he is wild and posed that way on his own!

Often misidentified as part of the antelope family, the Pronghorn (Antilocapra americana) is the only member of its family to survive the Pleistocene extinction. As the second-fastest land mammal on Earth, the Pronghorn can run as fast as 55 miles per hour and, unlike the fastest land mammal, the cheetah, they can maintain about 80% of that speed over several miles. This incredible force of speed means the adult Pronghorn no longer has any natural predators outside of human hunters.

In Alaska, the average caribou (Rangifer tarandus) loses four pounds of blood to mosquitoes. Alaska is home to 28 mosquito species which appear in quantities so great in caribou territory, that they are the primary driver of the caribou migration. Young caribou calves can die from mosquito bites, and moving to the coast where the winds keep the mosquitoes at bay helps ensure better rates of success for their offspring.

The moose (Alces alces) of Denali National Park are amongst the largest in the world. Bull moose here often hit 6.5-7 feet at the shoulder and can weight as much as 1,400 pounds. During the rut, these bulls will lost as much as 20% of their weight in pursuit of cows. While cows typically only mate with one bull every year, the males have been observed mating with as many as 25 cows in one season.

During the rut, bull moose compete with one another for the attention of the cows and the right to breed with them. They'll fight, using their powerful antlers to attack one another and defend themselves. Bull moose with the largest antlers, which they shed and regrow each year, are almost always the victors during the rut.

Like many other ungulates, the bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis) existed in abundance in the North American west prior to the arrival of settlers in the region. Early conservation efforts of the 1900s helped the threatened population rebound, but their modern-day descendants now face their own conservation issue: pneumonia. Passed to wild bighorn sheep herds from sharing summer grazing grounds with domestic sheep, an infection of just one animal in the herd can cause a mass diet of an entire herd. And, the disease is 100% fatal in lambs, wiping out generations of bighorns every year.

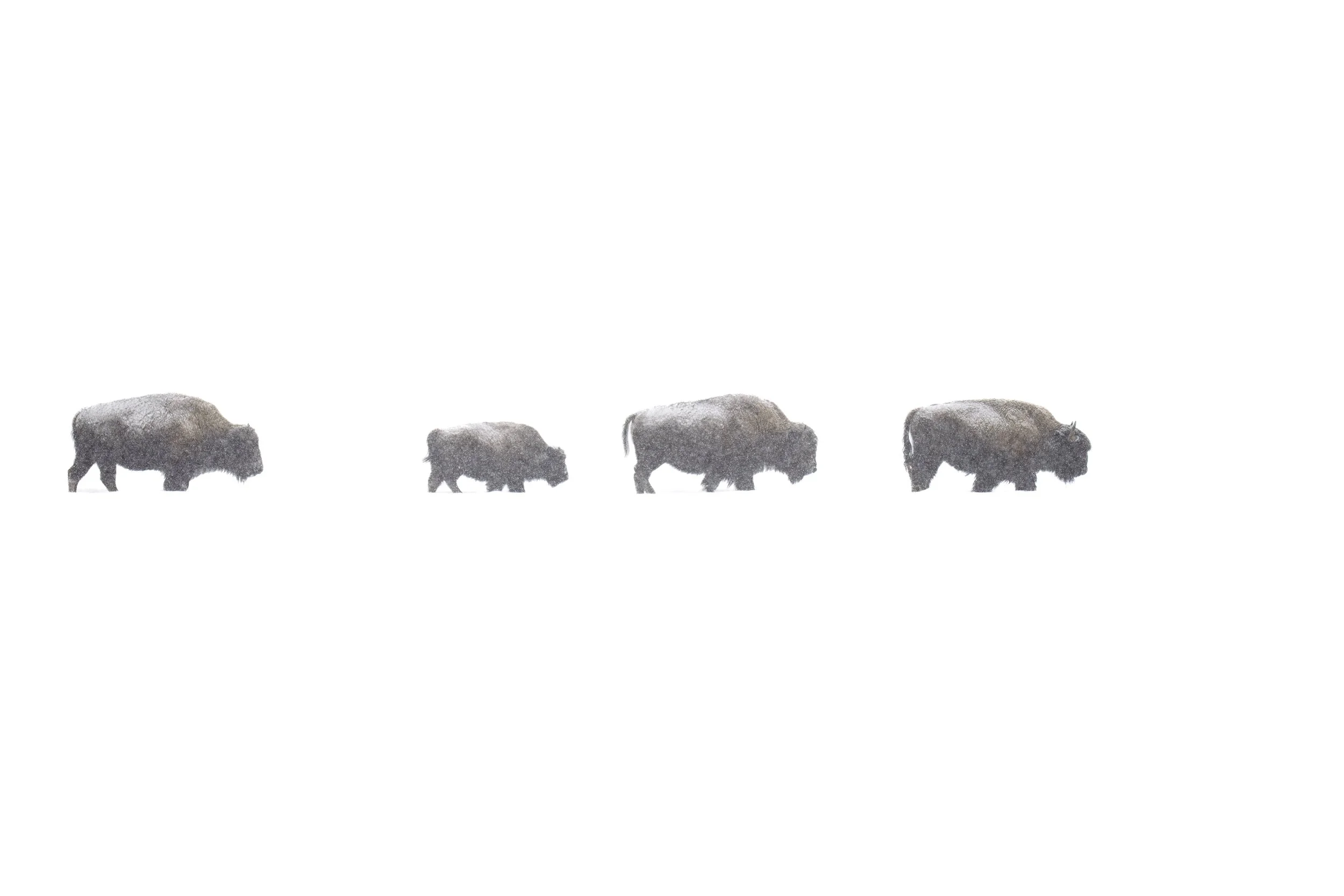

The American bison (Bison bison bison) of Yellowstone park have the distinction of being unique among the other bison herds around the United States. After almost going extinct due to settler overhunting and demand for their hides, the population of bison we see today are all descendants of a hybrid herd of bison (a combination of plains bison and mountain or wood bison that were introduced to the park in 1902.

The large humps that develop on the back of the American bison (Bison bison) are their neck and shoulder muscles, whose combined strength comes in extra handy during cold winter months. Face first in the snow, bison plow away the snow to get to the buried grasses.

In winter, the herds of bison are comprised primarily of females, with their young tagging along and an occasional young bull in the mix. While most species of herd animals are "selfish" herds, looking out for their individual safety, bison are one of two North American animals who create "cooperative" herds. When under threat, bison align their individual movements to create a more efficient escape strategy that benefits the entire group.

The thick, wooly coat of the bison is so well insulating that snow collecting on the backs of the animals will not melt from their body heat. In addition to their thick coats, their skin gets thicker in response to the cold and fatty deposits also aid in insulation, and they have the ability to generate body heat from the process of digestion.

A hearty species, American bison (Bison bison) live throughout the continent in places that experience both extreme heat and cold climates. While the grasses they eat are easily found in the summer months, they are buried under a blanket of snow come winter. The large hump on the back of the bison is made of powerful muscles, allowing them to plow through the heavy snow with their heads, exposing their food below. These massive ungulates create wildlife highways in the winter, as the herds move from place to place in search of more to eat. Their weight packs down the snow, helping animals like pronghorn and deer, who may otherwise struggle in deep snow, more ways to move. The bison also stir up the rodents of the subnivian zone—the layer between the ground and the underside of the snow—making it easier for animals like foxes and coyotes to snag some prey.

The elusive bobcat (Lynx rufus) mostly feasts on small mammals like hares, voles, squirrels and some birds like grouse and wrens, but will take down a deer or pronghorn if the right opportunity comes along. With large prey that cannot be eaten in one sitting, like this mule deer, bobcats will cache their food, covering their food with snow, leaves, and other natural material. This helps keep scavengers away from their food, though the bobcat will often rest near their food cache to defend it if necessary.

Beneath its fiery coat, the American Red Fox (Vulpes vulpes) hides a toolkit of survival strategies, perfectly tuned for winter. These small canids are masters of the pounce—a technique called “mousing,” where they leap high and dive nose-first into the snow to catch prey hidden beneath. They can detect the sound of a scurrying mouse buried deep in the snow, and some studies suggest they align their hunting direction with the Earth’s magnetic field to increase their accuracy.

When tidewater glaciers calve icebergs into the water, harbor seals (Phoca vitulina richardii) take advantage of all they have to offer. Using the icebergs for resting, molting, giving birth, and raising their young, harbor seals have a seasonal loyalty to the tidewater areas that provide them with protection during sensitive times. Like this harbor seal, these marine mammals will often haul out on icebergs to ward off attacks from aquatic predators. Climate change researchers and biologists are studying how the rapid retreating of glaciers impacts harbor seal behavior and their life span.

The North American porcupine (Erethizon dorsatum) can be found all over the state of Alaska, but these primarily nocturnal animals are experts at remaining out of sight. These vegetarian rodents enjoy a diet consisting of willow bark, spruce needles, the inner bark of the birch trees, and many of the leaves of aspen and cottonwoods. These plant-based meals are low in salt, however, requiring the porcupine to seek out natural salt licks to compensate. As a result, it isn’t uncommon to see them roaming rocky shores during the daytime, especially during the long summer sunlight of Alaska.

At first glance, the Brown-throated three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus) appears to have "claws" that help them climb, but these are actually elongated, curved phalange bones. A keratin sheath covers the bone.

Largely considered the most intelligent of the New World monkeys, the White-faced capuchin (Cebus imitator) monkey is an adept problem solver and quick learner. In Panama, these monkeys have been observed using rocks as a hammer to open small snails and coconuts. They also rub their fur with certain fruits, leaves and ants. While the exact reason is unknown, the hypothesis is doing so helps keep the parasites at bay.

Tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla) forages in a grassy area, showing its distinctive tan head and legs with a dark body. This natural habitat image captures wildlife behavior and peaceful surroundings.

A jaguar lying in dense green foliage, with only part of its body visible and its face peering out, surrounded by leaves and shadows.

The jaguars (Panthera onca) of the Pantanal region of Brazil aren’t afraid of water, and in fact, will often use it to their benefit while hunting their favorite prey - the caiman. Using dense mats of hyacinth leaves as cover, jaguars will often sneak behind caiman resting on the water or the shores, ambushing their soon-to-be meal.

Ecotourism and interest in seeing jaguars (Panthera onca) in the wild has played a key role in driving the economy of the northern Pantanal region of Brazil. Conservation organization Panthera, which works to mitigate conflict between these apex predators and local communities and ranchers, found that jaguar-watching tourism can bring in over $6 million more than the financial damages experienced by ranchers losing their cattle due to depredation.

The Pantanal, the largest topical wetland system in the world, is a biodiversity hotspot and home to one of the highest densities of jaguars (Panthera onca) in the world. Over the last few decades, the jaguar has come under intense pressure from habitat loss and fragmentation, resulting in a loss of almost 50% of its geographical range.

A jaguar swimming in water with only its head visible above the surface.

In the wetlands of South America, the Brazilian caiman (Caiman crocodilus) stands as both predator and protector of its ecosystem. During the breeding season, these remarkable reptiles show their softer side. Females build intricate nests from vegetation and mud, carefully laying their eggs in the safety of these natural incubators. Even after the eggs hatch, the mother remains fiercely protective, often carrying her hatchlings gently in her jaws to the water.

A giant river otter eats an eel in the Pantanal region of Brazil with warm, golden light and a blurred shoreline, capturing a calm wildlife moment.

A close-up of a giant anteater with a cub lying on its back and resting on its head.

A burrowing owl with bright yellow eyes stands on the ground amid grass and dirt, with a blurred natural background in Brazil.

Colorful blue and yellow macaw in flight against a blurred green background.

Colorful red and green macaw flying through the air with dark background.

Black-collared perched on a weathered post in a dim wetland morning light setting. The reddish brown plumage contrasts with a dark background, conveying alertness and solitary majesty.

Deep in the boreal forest, where spruce and fir dominate the landscape, lives one of North America’s most elusive predators, the boreal owl (Aegolius funereus).

Most people will never encounter this 8-inch tall raptor because their lives are tucked away in forests that few humans traverse. But during irruption years, when their preferred food source, the red-backed vole, experiences a population collapse, these owls journey southward in search of food.

A bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) demonstrates its agility in mid-air, changing course with an effortless twist of its wings. This powerful predator can shift direction instantly, making it a master of aerial maneuvers. These birds can reach speeds of up to 100 mph during a dive, and strike with lethal accuracy thanks to their high-resolution eyesight. The eyes of a bald eagle contain two foveae, which allow them to see both forward and to the side at the same time. Additionally, their eyes contain over one million cone cells per millimeter, which allow them to see small prey from as far as two miles away. For comparison, the human fovea has about 200,000 cone cells per millimeter.

The overall population of trumpeter swans (Cygnus buccinator) has rebounded in the decades since they were driven to the brink of extinction, there is one trumpeter swan population that is still holding on by a thread. The swans calling Yellowstone National Park their home, like this bird, have seen their numbers dwindle to just 28 swans in 2022. A classic example of “trophic cascade,” this specific group has been impacted by the introduction of lake trout to the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem back in the 1990s. Not native to that particular ecosystem, the lake trout soon decimated the number of native cutthroat trout, completely changing the dietary habits of fish-eating birds and bears, who depended upon the cutthroat trout as a dietary mainstay. Soon, those species turned to other sources of food, like swan cygnets, as a replacement food. To this day, it is required that all anglers keep any lake trout they catch as part of the ongoing lake trout suppression efforts.

Great grey owls, the royalty of the boreal forest, are an absolute marvel. With asymmetrical ears situated near their large disc-shaped faces, hearing is the superpower of this incredible bird. With their remarkable hearing, they can locate a tiny vole scurrying about the subnivean (under the snow) zone as far as 325 feet away and under as much as two feet of snow.

Once the owl locates their next meal, they silently fly to a location directly above it and hover for as long as ten seconds before punching through the hard snow-top, talons plunging deep into the snow to catch the unsuspecting vole.

The sandhill cranes (Antigone canadensis pratensis) of Florida are a little bit different than other sandhil cranes found around North America. This population, unlike the others, does not migrate and stays in Florida all year long. Each winter, these 4,000-5,000 residents are joined by about 25,000 cranes migrating in from other locations. Often found close to human development, these crimson-capped birds are a state-threatened species due to car collisions and habitat loss.

The Western Grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis) turns its breeding season into a spectacle of grace and coordination. Famous for their elaborate courtship rituals, these birds perform a stunning “rushing” display, where pairs run side-by-side across the water’s surface, their movements perfectly synchronized. It’s not just for show—this display helps strengthen pair bonds and signals their readiness to mate. Once bonded, Western Grebes build floating nests anchored to reeds or vegetation in shallow lakes. Both parents share the responsibility of incubating the eggs and raising the chicks, which often ride on their parents’ backs to stay warm and safe during their first few weeks of life.

A bald eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) perches on a piece of driftwood in the Kenai peninsula of Alaska. This precision hunter stands ready to defend its territory or claim a meal as the sun begins to dip behind the horizon.

Though the International Ornithological Committee classifies this bird as the black-necked grebe (Podiceps nigricollis), in North America it is still referred to as the eared grebe. While the eared grebe is among the most abundant in the family, its population is still highly impacted by habitat loss. This grebe relies upon having several staging areas during migration season, and changes to the habitat in these areas can have a significant impact on this bird. The prairie potholes of the upper midwestern region of the United States play a critical role in the health and survival of the eared grebe population

Larger than other species of grebes, the red-necked grebe (Podiceps grisegena) loves northern coasts and marshes, especially during breeding season. Striped young position themselves on the feathered crib of the adults’ back as they learn how to forage for insects and small fish.

A Common Loon (Gavia immer) glides across a calm lake, one downy chick nestled on its back while another paddles closely alongside. The still water reflects the lush green foliage of the surrounding forest, creating a serene scene of early summer. Loon parents share chick-rearing duties, with both adults taking turns carrying their young to keep them warm and safe from underwater predators.